I kind of put this thing on the backburner while life got crazy. Life is a little less crazy now and I'm noticing I'm still generating hits, so it seems there are at least a couple people that find these useful. This is one is going to be a little less involved than other articles. No crazy scientific citations because honestly, programming is largely opinion.

Niche Programming

The problem with programming with velocity is there are a million ways to implement it, but really no working examples of how to put it all together. That's not the case with percent based programming. There's plenty of templates that use percent based programming to progress and peak for a meet. There's periodized models, cyclical progression models, undulating models, and concurrent training protocols.

Special note: when I say "concurrent training" I mean training for strength and hypertrophy at the same time. Or I mean doing high rep work and low rep work at the same time. Some people might say that's the same thing as "conjugate training," but that's kind've a loaded term that tends to imply speed work, max effort days, and a bunch of other things I'm not trying to convey.I guess the first question is whether we need to re-invent the wheel or we can just modify something already out there? I'd say it's better to start from a known area and slowly venture into the unknown. Or better yet, how did Mike Tuscherer start when he made RPE? I'd guess it's no different than the process he began when developing RPE to prescribe load.

I think percent based training is the easiest place to start, so let's start there.

Parallels with Percent Based Training

This seems easy enough because all you have to do is sub out a percent of 1RM with a corresponding velocity. If 65% is 0.84 m/s and 95% 1RM is 0.32 m/s, then all you have to do is substitute the two. Once you have that, you can generally follow normal percent based training approaches. Maybe the most ubiquitous way to implement this is block periodization.

With block periodization, you see dedicated blocks of volume and intensity. Early on you generally see lower intensity and higher volume. Late into the cycle, you see higher intensity and lower volume. You could just straight out "translate" from intensity to velocity with some success in this case. But this is only one example of how to implement velocity into a percent based training program. One issue with this programming style is 1RM is assumed to be constant through a whole training cycle, so velocity alleviates that. If you get 3% stronger before you update your 1RM, it doesn't matter because we assume velocity scales with intensity. So if 65% moves at 0.84 m/s, then we can assume whatever weight is moving at 0.84 m/s is your current 65%. Having certainty that a given weight is 65% is also assuring because you also know what 100% 1RM is.

|

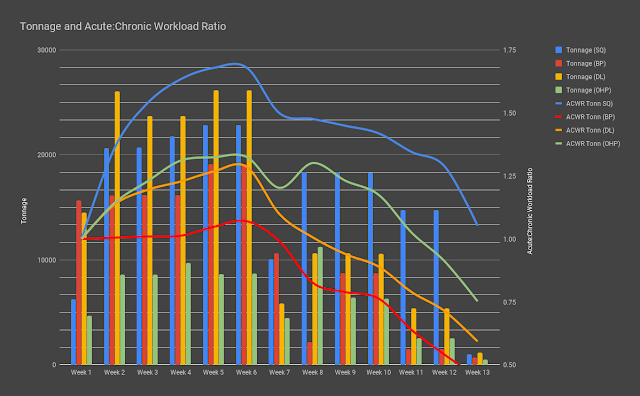

| Here's the same data represented as tonnage, along with acute:chronic workload ratios. |

There's also cyclical type programs, daily undulating programs, and concurrent programs.

A cyclical program would be something like 5/3/1 or the Juggernaut Method. These are kind of like really, really short linear or block periodization programs. Instead of taking 3 or 6 months to get to higher intensity work, you just progress to that within a shorter span of time. Much the same, you can substitute the percentages for velocities. The problem with many of these types of programs is they rely on AMRAP (as many reps as possible) sets to set increase a training max, but velocity functions in the same way. These AMRAPs empower the program to give you volume commensurate to your progress and a method to increase your working weights. Unfortunately, they're also a training obstacle. Without velocity, we have no way to gauge progress and no way to increase training load except through AMRAPs. With velocity, we can still follow the program as written, update training max in real time, and swap AMRAP sets for more training volume since the AMRAP sets offer nothing that velocity isn't already giving us. But maybe AMRAP sets are fun, so maybe you want to keep them in anyway. The point being is that there's no reason to go for an AMRAP if you have another metric to guide progression, like velocity. Doing an AMRAP is likely more training stress, so you could choose to do it as originally intended for no additional benefit (since velocity is driving progression), or do something else in lieu of it to ensure you have somewhat comparable training volume without the extraneous fatigue associated with an AMRAP set. And that's important, because high exertion work has limited and circumstancial utility.

Then there are programs that essentially train strength and hypertrophy concurrently. The first example of which is daily undulating periodization (DUP). This works kind of like a "heavy, light, medium" training cycle (HLM), where you're doing a mix of intensities and volumes throughout a week, given that intensity is inversely related to volume. So if it's higher intensity, there are fewer reps per set. If it's lower intensity, there are more reps per set, and so on. Both of these can be set up in a percent based program, but recently there have been RPE versions. In both cases (HLM and DUP), you can have designated intensities to hit for a prescribed number of reps. Just take the velocity equivalent of that intensity and hit it for the target repetitions.

It seems like HLM is gaining traction again, but it's essentially re-branded DUP. Updating DUP with RPE seemed like it essentially killed the training model's popularity, but it's still a valid training idea. For a while, DUP seemed like it was flirting with the idea of "daily 1RM" training. This seems like the opposite approach to augmenting 1RM as cyclical programs seem to take. Rather than setting rep PRs and updating your training max, you're updating 1RM and attempting to hit them for higher volume sets. Both methods impose a training obstacle that's really only essential because you don't know the current status of your 1RM. RPE seemed to integrate into this seamlessly and I could argue that it's become central to RTS's "top set" method.

It's also worth noting you can have linear periodization with a DUP program. Instead of having something like a week of 12/8/4 throughout you can have a block of 12/10/8, then linearly reduce that to 10/8/6, 8/6/4, and peak with 6/4/2 rep schemes. The overall net effect is a linear decrease in volume and a linear increase in intensity. Not to diminish what DUP is, but it's value is in it's versatility and simplicity.

Another system that uses a concurrent training approach is GZCL (here's a link to when MegSquats was doing GZCL and a link to Cody Lefever's/GZCL's website). This seems to be only popular on the internet though. Much like 5/3/1, there are a hundred versions, so I'm only going to talk about what it generally does. The main idea is to complete high-intensity work, moderate intensity work, and low-intensity work all within the same session. Usually, the low-intensity work is an accessory, the moderate intensity work is a close variation, and the high-intensity work is a main lift like a competition squat, bench press, or deadlift. Many people also throw in overhead press, but otherwise, it's a quintessential "powerbuilding" program. And once again, AMRAP sets are used to update your training max.

Let's just throw it out there that overhead press is only popular among powerlifters because of Wendler and Rippetoe. For most people, it actually doesn't help the bench press. So I guess my question is: why the hell are you training the overhead press in a powerlifting program? You don't need to have the overhead press unless you want it in your program. Having bench press as the tested event in powerlifting competitions is completely arbitrary, but it's not changing any time soon. I don't know why people came to value the overhead press more than something like a row or a pull up, but it did. Pulls are damn cool. Why do people neglect their pulls? It actually helps out your deadlift and bench press. I have nothing to support that, but I'm pretty sure it's true. Any case... the overhead press is a stupid, garbage person lift. Also, Mark Rippetoe is a dinosaur that doesn't know how to train anyone except novices, and arguably he doesn't even know how to train them well.

In all of these methods, you are eliminating the need for SOMETHING that previously served as a metric for progress. We no longer need those because we have velocity - at least in theory. With linear and block periodization programs, we need to update 1RM somewhat regularly, maybe at the end of "blocks," monthly, or whatever interval. With DUP or cyclical programs, you're also relying on some other metric. The problem is these methods rely on a singular performance. If that day was good, your training max is inflated beyond your training capabilities. If that day was bad, then you're suppressing your training max until you have another opportunity to update it. Largely, this isn't an issue to begin with because the reps assigned normally allow with some leeway so you're never hitting a 5RM for 5 reps. You're always leaving something in the tank by artificially reducing your training max or underprescribing reps so there are some reps left in the tank. In my opinion, both of these are just workarounds and do come to the detriment of training. If you could just prescribe the right weight on the bar for the right number of reps to begin with, you could do away with a lot of these if you had some way to figure out what the right weight and reps were to begin with.

Actually, isn't that exactly what velocity is supposed to do anyways? My first attempt at making an actual program with velocity was with a concurrent program. I used a GZCL ultra high-frequency template and just replaced the percentages with velocities. Because there wasn't any need for the AMRAP sets. It carried me along well enough to increase my total by 60 kg, so I can't say it was a bad training decision. The main problem I had with this is percent based training assumes proximity to failure is always the result of the intensity and reps. There's nothing to account for a rapid onset of fatigue. In those situations, you have to just figure out how to make decisions on the fly.

Adapting RPE Training

RPE is much easier to adapt. One of the recurring themes with percent based training is there needs to be some evaluation metric in order to update your training max. With RPE, your max is assumed to be fluid, so training and testing tend to be ever-present. Another great factor in this is you have two things to reference.

Let's just start with a prescription of 10 reps @ 7 RPE. This means you need to find your 13 RM and do it for 10 reps. Put another way, you need to find a weight that you can do for 10 reps and feel like you have 3 more in the tank. A final way to express it: do ~65% for 10 reps and you will probably have 3 reps left in the tank.

I know that 65% has an initial velocity of 0.84 m/s, and I know that 7 RPE has a final velocity of 0.32 m/s. This way I can do singles at an ever-increasing weight until I find something that moves at 0.84 m/s. Once I do that, I just do reps at that weight until I reach 0.32 m/s. If I get more than 10 reps to get to that point, this is likely a lift that requires a custom RPE chart. In all actuality, I'm probably just going to take a guess, hit 10 reps, and if it's faster than 0.32 m/s I'm going to add weight until I'm in the ballpark.

In any case, with RPE programs, in general, they aren't uniquely different than percent based programs other than how they prescribe load. It's perfectly possible to build out a linear periodization program with RPE. In fact, I believe this is the approach The Strength Athlete and Calgary Barbell's generalized intermediate programs take. Both approaches seem to be hybrid percent based and RPE programs. I've done my best to represent how those programs appear based on some basic deductive reasoning, but I think the output of Calgary Barbell's program looks something like this:

This seems like intensity linearly increases over time, but volume and relative intensity undulate across the weeks. Generally, most percent based programs tend to increase relative intensity in parallel to absolute intensity, but Bryce interesting attenuates relative intensity to allow for undulating volume. This process seems interesting since the outcome is meant to drive strength, whereas most classical periodization models tend to assume strength is meant to lead into power development. Most people developing strength from a classical periodization perspective tend to just lengthen the classical model and exclude the power development phase.

But you can generally get even something more akin to a linear or block periodization model using RPE. RPE is just the prescription method so the overall program can reflect whatever progression scheme you want. Barbell Medicine tends to program close to what a linear periodization model or block periodization model tends to prescribe. People tend to assume BBM is derivative of Reactive Training Systems, but hearing RTS's progression system described makes it sound much unlike traditional periodization models. I wish I could describe how this is likely a result of Bondarchuk's periodization influence, but like most others, I can't understand Bondarchuk's ideas even after reading and re-reading his books. Any case, here's a data dump of BBM's periodization.

A brief aside: strengthlifting as a competition is a lower body strength competition. Say whatever you want about whether the bench press or overhead press being the best demonstration of upper body strength, but strengthlifting has a huge issue of bias towards lower body strength. In a typical powerlifting competition, the squat makes up 35% of your total, the bench press 25%, and the deadlift 40%. Advantages in morphology, like having short or long arms, kind of give advantage to one lift (like bench) and take away from another (like deadlifts). Take that vs strengthlifting: the squat is 38% on average, the OHP is 17%, and deadlift is 45%. The overhead press has such a dimished effect on your total that morphological advantages in the deadlift have less to lose in the OHP. So that's the secret to strengthlifting: just have a strong lower body and do the minimum to develop pressing strength. Sounds pretty typical for Starting Strength's faults: favors lower body over the upper body. If it hasn't become obvious, I hate Starting Strength.

However, it's worth mentioning that most of the ideas on periodization are very generalized. They don't empirically work for all modes of training and they attempt to generalize how to organize and progress training for field sports, also in general terms. In such cases, volume, intensity, and exertion are very generalized terms that sometimes refer to completely different metrics, like distance ran, speed which it was run at, and perceptual feeling of how hard the effort was.

And that's maybe one of the harder things to deal with if you're going to be dogmatic. You can only generally apply training theory from one sport to another. Like generally applying track and field to powerlifting (Verkhoshansky). Or generally apply training theory from rowing to powerlifting (Issurin). Or weightlifting to powerlifting (Prilepin, Laputin, and Medvedyev).

The great exception here is RPE program structure seems to adopting an Emerging Strategies approach. So what does an emerging strategies template look like? It's probably impossible to make a generalized emerging strategies template. That's like saying you want a generalized template that's individualized. It doesn't work like that. And if you've ever heard a coach tell you about their case studies with athletes, you'll often here them explain why they depart from textbook periodization approaches to better fit their plan to their athletes. They're essentially interpreting the athlete response to the dose of training, making inferences on what the next best step in the progression is. That sounds much like how adaptive emerging strategies attempts to be except with a lot less reliance on an initial plan. Are these differences consequential? In my opinion, no. But then again I have no allegiance to any programming style and I make fun of everything.

So what was the point of this whole section? Basically to show you it's mostly a distinction without a difference. All it is is another way to prescribe load and another metric to collect. I think that metric is important, but that's just me.

Getting to the point

So then what does RPE offer that percent based training doesn't programming wise? With percent based training, intensity (%1RM or % of training max) and volume (reps and sets) are prescribed with exertion (RIR, RPE, or relative intensity) largely assumed. With RPE, volume (reps and sets) and exertion (RPE) are prescribed and intensity is assumed. Generally, we can assume that intensity is a valid inference before acute fatigue sets in. Let's take something like 8 sets of 4 reps at 8 RPE. Initially, intensity is likely going to be near 84% 1RM. The problem is that keeping weight the same is it takes a lot of work capacity, so you're eventually going to drop the weight. Does that mean intensity is always 84% in the moment, or do you base intensity off the original weight and corresponding 1RM?

Let's take the opposite with percent based training. Let's do 84% for 8 sets of 4. Or 8x4 @ 84% in short. Let's never change that weight. Initial sets at probably going to feel like 8 RPE, or 94% relative intensity. As time goes on, that exertion (or RPE, or RIR, or relative intensity) is going to feel like it's increasing - because that's how acute fatigue works.

In either case, you have real-life circumstances failing to represent the training. The problem is most percent based programs only present the dose of training and ignore the response. RPE programs actually measure the response with the RPE system but requires you to interpret the data circumstantially.

So let's just get to the point of what two different programs look like. One was more like a percent based program. I would hit an initial velocity and use it's assumed equivalent intensity to do a number of reps. It was concurrent training (trained for both strength and hypertrophy), but both "training zones" or whatever increased linearly. My first lift started at 80% and increased linearly, and my rep work started at 60% and increased linearly. If I couldn't hit all the reps required, I just increased the number of sets. It was pretty gruelling. Here are some graphs that show you what it looked like. They were pulled from MyStrengthBook.

This all led into my first powerlifting meet as a 74 kg class lifter. My next prep I decided to take a different approach because ignoring RPE/RIR/relative intensity was grueling. Rather than planning off intensity (based on initial velocity), I decided to plan my training off of exertion (based on final velocity). This allowed me to plan more along the lines of someone who used RPE.

So does anything meaningfully change when you program with velocity based training? Not really. If you're having crazy fluctuations in 1RM or work capacity, maybe, but generally no. Velocity does 100% of what percent based training can do. RPE does 100% of what percent based training does. Velocity does 80% of what RPE does. And RPE does 80% of what velocity does. The only real difference is that last 20% of what velocity can do that RPE can't, which has only circumstantial utility. That 20% of what RPE does that velocity can't? Just add it on top of what RPE is doing.

So what's the point? It's kinda just that nothing makes any difference, nothing matters, and do whatever you want. Just stay away from Rippetoe and Starting Strength, because they straight garbage.

So let's just get to the point of what two different programs look like. One was more like a percent based program. I would hit an initial velocity and use it's assumed equivalent intensity to do a number of reps. It was concurrent training (trained for both strength and hypertrophy), but both "training zones" or whatever increased linearly. My first lift started at 80% and increased linearly, and my rep work started at 60% and increased linearly. If I couldn't hit all the reps required, I just increased the number of sets. It was pretty gruelling. Here are some graphs that show you what it looked like. They were pulled from MyStrengthBook.

|

| If it's not obvious, I really do use miniscule deadlift volume. I'm no Bryce Krawczyk. Squats are bae |

|

| And then here's everything together. Again, the accessory volume is calculated separately using this system. Again, 1RM wasn't updated regularly, so things look a little different. |

|

| For this I didn't have an accessory heavy period of training, so this is probably more directly understandable. |

|

| Here's the number of lifts represented again. As you can see, I continue to keep deadlift lifts on the lower end. |

Wrapping it all Up

So what's the point? It's kinda just that nothing makes any difference, nothing matters, and do whatever you want. Just stay away from Rippetoe and Starting Strength, because they straight garbage.